CHISINAU, MOLDOVA - OCTOBER 20: A camera set up to monitor voters at a polling station is online on October 20, 2024 in Chisinau, Moldova. Moldova holds its presidential election on Sunday, with incumbent pro-EU President Maia Sandu facing former prosecutor Alexandr Stoianoglo, backed by the pro-Russian Socialist Party, and nine other candidates. Voters will also decide in a referendum whether to amend the constitution to make EU membership an official national goal. (Photo by Pierre Crom/Getty Images)

Prebunking in Moldova – a pilot with punch

Disinformation, rapid technological developments, changing media habits and unstable revenue streams all have a negative impact on media outlets across Europe and challenge their ability to reach audiences. But in 2024, a pilot initiative in Moldova has set out to explore ways and formats to counter harmful narratives.

At a time when distinguishing false information from the truth is increasingly challenging, and where malign actors sow confusion and suppress groups in marginalisation, IMS and its partners are dedicated to reclaiming the digital space for truth and inclusivity. Crucially, IMS does not position itself as an organisation that directly combats disinformation. Rather, our work focuses on fostering safe societies in which human rights are protected. Achieving this requires reducing societies’ vulnerability to destabilising influences, including disinformation and aggressive propaganda. The goal is to empower individuals and local media to remain aligned with their own interests – to be interest-driven – and to act in ways that genuinely serve those interests.

IMS has worked in Moldova since 2022 to bolster the business viability of independent media, improve media policies and assist civil society in promoting secure and diverse information environment. In 2024, IMS launched M-MIIND, a mechanism to build capacity of independent media and offering ways to test and explore how best to build resilience against foreign information manipulation and interference (FIMI).

Several organisations took part, but safety considerations prevent naming them.

M-MIIND provided a space for those media organisations and to experiment with prebunking as a potentially more impactful way to address harmful narratives deliberately manipulating Moldova’s public discourse and information space.

Roman Shutov led the effort. He is an expert in disinformation and FIMI and has been with IMS since 2022. To better understand what took place in Moldova, he agreed to answer a set of questions.

We’ve heard about debunking lies and disinformation. You talk about prebunking, what is that exactly?

IMS adopts and supports a prebunking approach. This means we do not chase disinformation after it has already entered the information space and intoxicated public discourse. Instead, we aim to identify disinformation operations at early stages and ensure that fact-based content is delivered to audiences before they encounter disinformation. Typically, there is a window of about 36 hours between the onset of a disinformation campaign and its peak reach. We encourage our partners to use this time effectively to reach their audiences quickly with accurate information – so that the true story is heard first.

This requires a high level of awareness, ongoing research and constant monitoring of the information space to detect disinformation attempts in time. IMS collaborates with tech company LetsData, which monitors the information environment in Moldova. Their AI-based algorithm analyses online content 24/7 and generates automated alerts that help detect emerging disinformation threats or recurring harmful patterns. This strengthens our partners’ preparedness and enables rapid response to disinformation efforts.

There’s much talk about local media being the bulwark of democratic societies, but local media tend to lack resources. What did you do to ensure local media’s role in this initiative?

On one hand, resource support is clearly important, as producing content – especially high-quality and rapid-response content – requires investment from partners. However, this is not the only consideration. It is equally crucial to ensure that the mechanism is aligned with local realities, responsive to partners’ needs and tailored to the expectations of the target audience.

The model in Moldova underwent a complex evolution during its first 12 months. It was a continuous process of learning by doing, which required intensive feedback from local partners. In fact, the key to the model’s success has been its high responsiveness to partner input and their vision of how a rapid response mechanism should function in their national context.

Taking your thinking and strategy to practise – what main lessons have you learned?

Perhaps the first key lesson is that producing fact-based content is inherently more complex and slower than producing disinformation. We observe how malign actors are able to generate massive volumes of content in a very short time, saturating Moldova’s information space with manipulative and low-quality material. In contrast, our partners – as fact-driven and standards-based media – require more time due to the need for factchecking, editorial review and a more rigorous production process that ensures quality. As a result, one of their central challenges has been how to accelerate the production of high-quality, fact-based content to outpace disinformation.

This leads to a second lesson: if we want to effectively practise prebunking, we must adopt a “social media first” approach. Social media acts as an information fast-food – it is where content rapidly enters people’s news feeds and personal information bubbles. It is also a space that can be leveraged to establish fact-based narratives before disinformation takes hold. Importantly, disinformation actors also prioritise social media. FIMI attacks typically begin with social content to achieve immediate impact. This is why our partners prioritise the social media-first strategy in their response to FIMI threats.

How do you assess the impact?

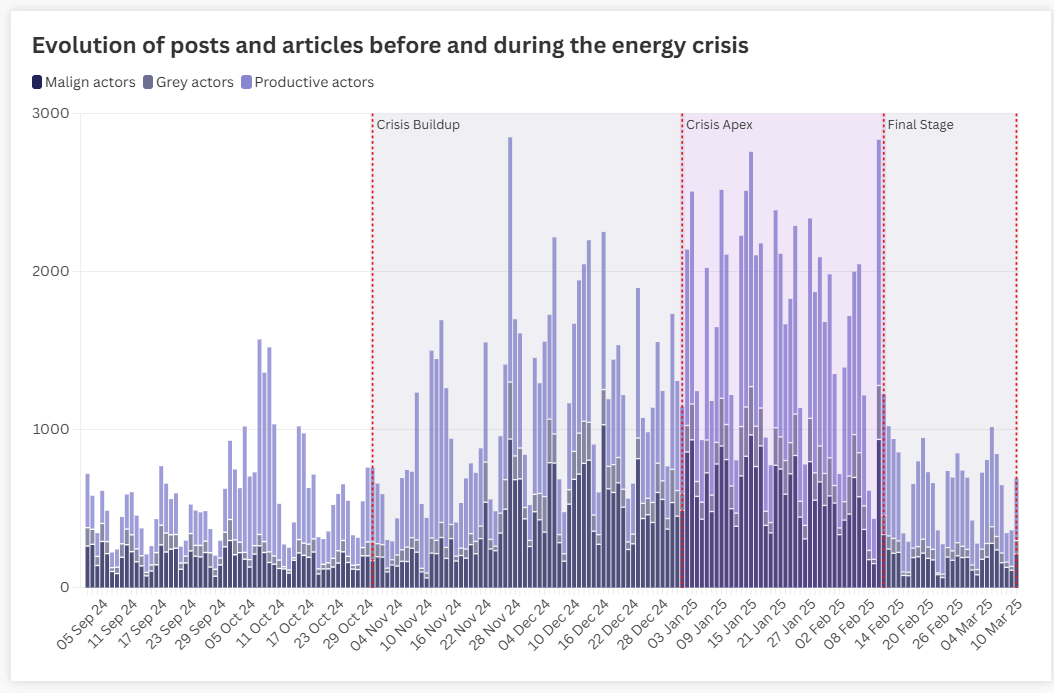

There are two dimensions of impact as I see it. The first relates to the extent to which key societal discourses – particularly those most vulnerable to disinformation and manipulation – are addressed through prebunking efforts. We assess whether our partners are able to anticipate and outperform disinformation in these sensitive areas. For instance, a recent example in Moldova was the energy crisis, which triggered a surge of information turbulence. Hostile actors sought to exploit the situation to discredit the government, undermine Moldova’s EU accession process and justify or legitimise Russian aggressive policies. In parallel, our partners worked to counter these narratives and mitigate the potential harm caused by such messaging.

The crisis initially unfolded with disinformation narratives in a dominant position. On average, disinformation stories were viewed twice as often as fact-based stories. This was the point at which our partners began to escalate their response – they mobilised efforts to counter the disinformation, reorganised their workflows – while we increased our calibrated support, research assistance and coordination among them.

This indicates that the voice of truth had become louder than the voice of disinformation.

By the time the disinformation campaign reached its peak, the fact-based narrative had already taken the lead – accounting for approximately 60–65 percent of the information landscape. This indicates that the voice of truth had become louder than the voice of disinformation. We observed a clear correlation between our partners’ intensified efforts, the support mechanisms in place, and the resulting impact.

The second dimension of impact concerns how effectively our partners serve specific vulnerable audiences – and the extent to which their influence and visibility within these groups increases. Here as well, we observed strong results. For example, during the gas crisis, one of our media partners experienced a twofold increase in traffic to its Russian-language platforms. This indicates that Russian-speaking audiences – who are often more susceptible to anti-Moldovan propaganda – began placing greater trust in, and paying more attention to, the fact-based content produced by our partner.

We were particularly encouraged to see that among the most viewed and engaged-with publications were those produced with our support during the energy crisis. For us, this demonstrates that these partners have grown more influential within the very audiences that are most in need of accurate and trustworthy information.

Can you give any examples of what these efforts may look like?

On 4 February, EU Commissioner Marta Kos visited Moldova, signing an agreement for new EU financial assistance aimed at strengthening Moldova’s energy independence and facilitating EU energy market integration.

LetsData monitored the information environment, expecting disinformation related to the visit. They vigilantly observed social media channels and the media discourse and alerted those collaborating with us, when coordinated disinformation efforts surfaced.

Malign actors attempted to frame the EU support package as conditional, biased and exploitative, while accusing Moldova’s government of media manipulation and dependency on western powers. Partners received near real-time reports on social media trends to track discreditation efforts and emerging attack narratives.

The coordination of fact-based actors proved effective, as they produced 81 percent of the content compared to the malign actors’ 11 percent. On digital platforms, fact-based actors reached over 44,000 views, while malign content generally failed to surpass 50 views. Telegram was the exception, where malign actors achieved 108,000 views compared to fact-based actors’ 32,000, highlighting a monitoring gap in that channel.

Your work is to counteract harmful narratives. Why is it such a strong priority and how is it done?

I would put it this way: our focus is not so much on disinformation itself, but on the vulnerabilities that make audiences susceptible to it. We ask a different kind of question – why do certain audiences believe manipulative narratives even when they have access to truth and factual information? Accordingly, we support and initiate research into these audience vulnerabilities – particularly the emotional and cognitive drivers that lead us to be susceptible to manipulation and disinformation. We explore how media can engage more effectively with the public interest and how it can contribute to reducing the influence of these drivers.

Disinformation is especially harmful during election times. What do you see as the key challenges to address?

Elections are merely the point at which hostile actors and manipulators harvest what they have been cultivating between election cycles. What they cultivate is deep-seated distrust – complete distrust in institutions, in the media, pervasive frustration, disorientation, intolerance, hatred, homophobia and a wide range of social divisions. These sentiments are nurtured constantly – 24/7, all year round. Elections simply serve as the moment when these dynamics are converted into full-fledged information warfare.

It is short-sighted to begin addressing disinformation only in the run-up to elections.

It is short-sighted to begin addressing disinformation only in the run-up to elections. Doing so ignores the extensive disinformation activities occurring in the interim periods and fails to address the underlying vulnerabilities of the population – vulnerabilities that are formed before elections and merely exploited during them.

Media care about guarding editorial independence. Do you see any obstacles to safeguarding independence if media engages in prebunking?

I see no risks associated with media outlets practising prebunking. It is a completely neutral and safe approach, which differs from debunking in that it does not chase disinformation after it has already spread and intoxicated audiences. Instead, it works proactively – delivering accurate information in advance so that audiences are protected. There is no political agenda behind this practice.

The only potential sensitivity arises when multiple partners engage in prebunking in a coordinated manner. In such cases, questions around editorial independence may emerge. IMS holds a clear position on this: any coordination must fully respect and safeguard editorial independence. Joint decisions made by media partners as part of coordination processes are never directives or mandatory actions. Each partner retains its own editorial stance and determines its policy on how to respond to any given disinformation incident. While we do encourage partners to synchronise efforts and share a common agenda, we never require them to produce specific content against their will.

You talk about a “whole-of-society approach” – what does that mean?

A whole-of-society approach means striving to ensure that every social group within society is served with fact-based information tailored to their needs and preferences. It means that no one is left uninformed or unreached by credible, engaging and accessible content. Importantly, this extends beyond news – we consider a much broader spectrum of informational and cultural needs, including entertainment, social content, personal stories, fiction and more.

This prompts us to ask: why are certain groups within society still underserved? Why are specific communities still misinformed, disinformed or misled? Why do some groups continue to propagate xenophobic or traditionalist views?

These questions highlight the need for a deeper understanding of different segments of society – their preferences, cultural fabric, lived realities, mentalities and media consumption patterns. We must consider how identity, cultural norms, material conditions and media habits are all interconnected.

From there, we ask: what kinds of content can we produce, and how can we deliver it effectively, to ensure that these groups are better informed and more meaningfully engaged?

When debunking disinformation you risk amplifying the harmful narrative. What is your advice to avoid that?

The answer is simple: we do not engage in debunking. Prebunking means that you do not repeat or directly confront the disinformation. Instead, you either fill the knowledge gaps that make people susceptible to disinformation, or you address the emotional patterns and other vulnerabilities that contribute to that susceptibility, thereby building greater resilience.

You do not challenge disinformation in a head-to-head battle. You do not enter into blame games or engage in “you’re the liar” dynamics. Instead, you tell your own story – a story grounded in facts and credibility.

CASE: NATO building a military base in Moldova

The narrative that NATO was building a military base in Moldova began circulating on 15 July through anonymous Telegram channels. This false claim quickly gained traction, accounting for 69 percent of public engagement on the topic. LetsData conducted an in-depth analysis of the narrative’s progression, monitoring its spread across five social media platforms and Moldovan digital media from mid-July to mid-August. The analysis revealed polarised discourse, with some claims suggesting the alleged base was intended to provoke Russia, while counterclaims emphasised its supposed economic benefits without military objectives.

The falsehoods appeared mainly on Telegram, with minimal coverage on other platforms, including a single YouTube video from a local TV channel. Telegram posts averaged 700 views each, and the most-viewed content reached 11,000 views overall. This early warning allowed stakeholders to take proactive measures to address the issue before it gained significant momentum.

By 26 July, the disinformation campaign intensified, with increasingly toxic rhetoric and broader dissemination. Despite ongoing efforts to debunk the narrative, a follow-up analysis on July 29 revealed that malign actors continued to dominate the discourse. Approximately 80 percent of the messages focused on the alleged construction of a “logistic hub in Ungheni”.

In response, LetsData recommended that media partners focus on producing more content in Russian. This advice stemmed from the observation that over 70 percent of the malign content was in Russian, while only two percent of the counter-messaging targeted Russian-speaking audiences. Closing this language gap was essential to effectively combat the disinformation.

Why does it matter?

This case illustrates the importance of early detection, strategic communication and coordinated efforts to address disinformation campaigns. By leveraging these approaches, stakeholders can mitigate the spread of false narratives and prevent their amplification.